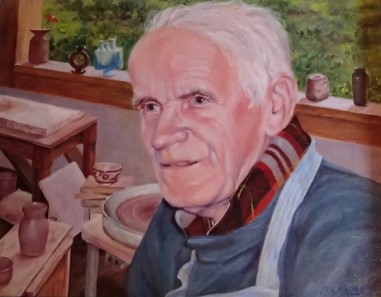

Edward Devlin

PART ONE: “WHAT DO YOU MEAN, YOU DON’T WANT TO BE A DOCTOR ?!”

The plate shown above is described by the auction house as, “Dedham pottery crackleware, very rare plate painted by Ned Devlin, Asian inspired scene, 1934. Indigo Registered stamp, artist signature and date. Estimated at between $1,250 and $1,750.” (2008 auction)

Edward Devlin was born in 1912, a Boston native, he grew up in a comfortable home. His father had as they say, “pulled himself up by the bootstraps” and through hard work and determination had become a dentist. It was presumed in the Devlin household that owing to all the advantages given them, that all of the boys would enter the professions, preferably becoming doctors. We can only imagine the conversation, when Edward announced to his father, that he wanted to attend art school. That being said, his father must have recognized that he had “shown artistic inclinations from an early age.” Edward went on to “graduate from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston where he received a scholarship for painting in 1929.” He also attended Massachusetts Art Institute and studied sculpture at the Copley Society.

Ed began his career in the 1930’s as a decorator at the Dedham Pottery in Dedham, Massachusetts. When he worked for Dedham, he signed his work as Ned Devlin. While there he created Chinese landscape designs among other motifs. Dedham had been founded by a fifth generation Scottish potter named Hugh Robertson, and operated from 1896 through 1943. It was known for its high-fire stoneware characterized by a controlled and very fine crackle glaze with thick cobalt border designs. A Yankee Magazine article says of Dedham that, “This homage to the raw beauty of nature was never more apparent than during the Arts & Crafts movement. Its back-to-nature aesthetic rejected the industrialization of the late 19th century and embraced a return to the simplicity of handmade goods. American artists heard this call of the wild and, so inspired, produced some of the finest decorative pieces ever made in this country. Beautiful ceramics were one of the movement’s greatest legacies, and among the most popular wares was Dedham pottery, made right here in New England. You likely already know Dedham pottery: that simple tableware with the bluish-gray crackle glaze and cobalt-blue border of flora and fauna. The charming patterns repeat in a right-facing (or, occasionally, left-facing) rotation. It’s reminiscent of Chinese export porcelain, but with a whimsical edge. Both modern and traditional in its appeal, Dedham pottery’s most recognizable border design, the crouching ‘Dedham Rabbit,’ doubles as the image for the company logo.” All of the designs were painted by hand by the artists at Dedham.

The Art Student League building in New York City. Notable Alumnae include Mark Rothko, Roy Lichtenstein, Georgia O’Keefe and Jackson Pollock.

After working at Dedham, Ed decided to head for New York City. While there, he was a member of the Arts Students League. Another member of the league, at the same time, was John Little, who studied there under Georg Grosz (a famous German expressionist painter who emigrated to America in the 1930’s,) and Hans Hoffman. Little was according to the New York Times, “an abstract expressionist artist who founded a New York company that made fabrics and wallpapers with designs inspired by abstract impressionism.” “In 1921, Mr. Little founded the fabrics-wallpaper company, which he called the John Little Studio. By the mid-1930’s the concern was attracting wide praise for fabrics that combined high-quality designs with affordable prices.” Little went on later to paint with his friend and neighbor, Jackson Pollock. Edward Devlin designed fabrics and wallpaper at John Little Studios, during the 1930’s, at the highpoint of the company.