The Bridge over Beaver Brook on Mammoth Road.

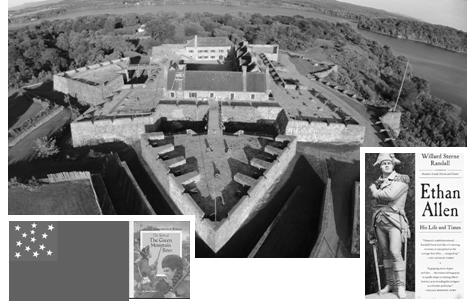

If you grew up in New England, one of your family road trips was likely to Vermont and New York, to see Fort Ticonderoga, and to explore the Ausable Chasm after ferrying across Lake Champlain.

“The capture of Fort Ticonderoga was the first offensive victory for American forces in the Revolutionary War. It secured the strategic passageway north to Canada and netted the patriots an important cache of artillery.”

“Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, together with Benedict Arnold, surprised and overtook a small British garrison at the fort, acquiring valuable weapons for the Continental Army. Arnold took command of Ticonderoga until he was relieved in June 1775.”

“Located at the confluence of Lake Champlain and Lake George, Fort Ticonderoga controlled access north and south between Albany and Montreal. This made it a critical battlefield of the French and Indian War. Begun by the French as Fort Carillon in 1755, it was the launching point for the Marquis de Montcalm’s famous siege of Fort William Henry in 1757. The British attacked Montcalm’s French troops outside Fort Carillon on July 8, 1758, and the resulting battle was one of the largest of the war, and the bloodiest battle fought in North America until the Civil War. The fort was finally captured by the British in 1759.”

“During the American War for Independence, several engagements were fought at the five-pointed star-shaped Fort Ticonderoga. The most famous of these occurred on May 10, 1775, when Ethan Allen and his band of Green Mountain Boys, accompanied by Benedict Arnold, who held a commission from Massachusetts, silently rowed across Lake Champlain from present-day Vermont and stormed the fort in a swift, late-night sneak attack.”

“Months later, George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, sent one of his officers, Colonel Henry Knox, to gather the artillery left at Ticonderoga and bring it to Boston. Knox organized the transfer of the heavy guns over frozen rivers and the snow-covered Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts. Mounted on Dorchester Heights, the guns from Ticonderoga compelled the British to evacuate the city of Boston in March of 1776.”

“The capture of Fort Ticonderoga was the first offensive victory for American forces in the Revolutionary War. It secured the strategic passageway north to Canada and netted the patriots an important cache of artillery. n 1775, Fort Ticonderoga is garrisoned by a small detachment of about 50 men and has fallen into disrepair, but its value—both for its location and the arms it houses—is well known. Patriot Benedict Arnold persuades the Massachusetts provisional government to give him a commission to command a secret mission to capture the fort. But Arnold soon learns that Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys are already on their way north towardward Ticonderoga with the same intention. Arnold is warned that although Allen has no official sanction for his planned attack, his loyal men are unlikely to take orders from anyone else. Arnold feels that he should lead the expedition based on his formal authorization to act from the Massachusetts government. He and Allen come to an agreement about sharing command, despite the objections of some of Allen’s men. Ultimately, their force includes about 100 of Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys and 50 other men recruited throughout Connecticut and Massachusetts.”

“By 11:30 p.m. on May 9, the men are ready to cross the lake from what is now Vermont to Ticonderoga. The small boats do not arrive until 1:30 a.m. and they cannot accommodate the entire force. Eighty-three of the Green Mountain Boys make the first crossing with Arnold and Allen. As dawn approaches, Allen and Arnold, worried about losing the element of surprise, decide to attack with the men at hand.

American victory. Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, together with Benedict Arnold, surprised and overtook a small British garrison at the fort, acquiring valuable weapons for the Continental Army. Arnold took command of Ticonderoga until he was relieved in June 1775.”

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/fort-ticonderoga-1775

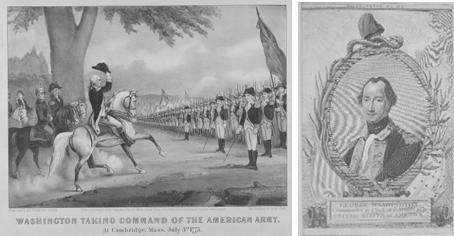

“George Washington arrived at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia on May 9, 1775. Immediately he was placed on several committees that handled military preparedness in the colonies. Washington had a respected military reputation based on his time serving in the French and Indian War, lending him respectability and a certain level of expertise. One of Washington’s first acts included designing a buff and blue colored uniform sewn by an indentured servant at Mount Vernon named Andrew Judge; Washington wore it throughout his time in Philadelphia.”

“The selection of a commander of the militia forces gathering outside Boston after the battles of Lexington and Concord constituted an important priority for the Congress. The New England forces lacked guns, ammunition, training, and most importantly leadership. Several New England congressmen believed that their officers should command the army surrounding Boston. Others thought that an outsider in command would truly make the militia a “Continental” army. Washington commanded a loyal following among many of his fellow delegates. Those unfamiliar with his politics and reputation sounded out the Virginia delegation for information.”

“ ‘A need for unity and common cause among the colonies motivated delegates to consider Washington. An army drawn from all of the colonies with a Virginia commander would make the Massachusetts cause a struggle shared by the entire continent. Washington’s unanimous choice signified the beginning of a process to create a national military force.’ Washington’s selection made sense for several reasons. To make the rebellion a truly continental endeavor, the participation of Virginia—the wealthiest and most populous colony—was essential. Congress sought a commander with direct combat experience, and few had more than Washington. At forty-three, he was vigorous and young enough to survive the long campaigns of a protracted conflict. Lastly, Washington’s fellow Virginians convinced many congressmen of his singular determination to the patriot cause.

Politically, Washington was a moderate revolutionary; a sober leader determined to defend colonial rights. Washington’s presence also helped his cause; several contemporaries described his appearance as majestic. Benjamin Rush explained that, ‘He has so much martial dignity in his deportment that you distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among ten thousand people.’ ”In his statements after his appointment, Washington pledged obedience to the civilian authorities in Congress. He declined a salary, asking only that he be reimbursed for expenses he accrued during the conflict. In his acceptance speech of June 16, Washington sounded the appropriate chords of humility in stating, ‘I am truly sensible of the high Honor done me in this Appointment… I do not think myself equal to the Command I am honored with.’ In private letters, Washington thought himself unworthy of the monumental task he faced.”

“Encountering Patrick Henry after the vote, Washington’s eyes filled with tears as he told his fellow Virginian “Remember Mr. Henry, what I now tell you: from the day I enter upon the command of the American armies, I date my fall, and the ruin of my reputation.” Before speeding to Boston, Washington purchased several texts on organizing and leading large armies.” James MacDonald, Ph.D. Northwestern State University. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/appointment-as-commander-in-chief

If you’ve been down Lowell Road recently, you must have seen the recent improvements of the Conservation Commission to the Fessenden Mill property which was acquired from Murdock Mackenzie. It’s a very beautiful spot. You can still see the outline of the foundation to the mill, which was the largest manufacturing building in town. The mill was originally powered with water rights from Cobbett’s Pond. The first grist-mill was established here before 1790. The larger mill building was built in 1871. Cloth was manufactured here and later witch-hazel.

The three following letters, dated at Medford, Mass., were written by Robert Dinsmoor to his parents the first winter of the Revolutionary War. He says: “I was an early friend to our Revolution and Independence, a true Whig; and had the honor of being a solider in the American army under the illustrious Washington. I wish to preserve the letters for antiquity’s sake:” (Robert Dinsmoor was 18 years old at the time.)

Medford, Mass., Dec 20th, 1775

My dear father:

In the first place I am well, for which I have reason to thank God who hath hitherto preserved me. The regulars fire last Sunday night from Bunker’s hill to Leechmore’s point at our men who were entrenching there, and a few bombs came from Boston to them, but they did but little damage, only wounded two men and killed one ox. Capt. Gilmore’s* company was there, and as uncle Robin Dinsmoor was wheeling a Barrow load of Sods, a cannon ball came along and split an apple tree close by his side, but did not hurt him. Some cannon fired from Cobble hill which made the Hornet’s nest* remove from Leechmore’s point. Our company has not been upon are duty yet, but ten of them are called upon to go upon the Piquet guard tomorrow at Plow’d hill. I have told you considerable, and must conclude, for want of paper. But I must not forget Lieut, Gregg desires in a particular manner to be remembered to both you and mother and to my sweetheart, if I have any —and so do all the other officers — give my respects to my friends, especially those who thought worthwhile to come a piece with us. Let Master McKeen know I do not forget him. Remember me by all means to my ancient Grandfather and Grandmother. I must conclude with sincere love to you, my Mother, Sisters, and Brothers. Your dutiful and affectionate son,

Robert Dinsmoor.

Ens 11 William Dinsmoor.

P.S. I am in the mess with the Officers the same as I was at the Great Island.

* A British frigate. (Which is odd since there were no British frigates by this name, however the Hornet and the Wasp were ships in the American navy placed into service at about that time.)

Medford Jan. 2, 1776

I enjoy perfect health at present. Thanks be to a kind Providence. I have nothing strange to write to you, except that orders are this minute come from the General that our company shall be freed from other duty, to go chop wood for the Army about half a mile from our Barracks — when we are cold! I sent a letter to you byColonel Moore. We are stationed in a Brick house about half a mile down the river from the Town. This minute Abraham Plunkett* came in with fifteen letters, which revives my spirits. I am sorry that you had so much trouble with your letters — and Jonny says Colonel Moore carried my letters to Derry which he promised to leave at Capt. Gilmore’s. I am glad you are all well.; let mother know that I received her letter very joyfully. I have gotten but one letter from you since I came here. Last Friday night General Sullivan gave orders to his under officers to enlist a party of volunteers, such as were willing to make a push at Bunker’s hill, and burn a number of houses on Charleston neck; according to Capt Reynolds and Lieutenant Gregg and 21 members of our company went with Arms and Ammunition. The whole number that went was about three thousand, provided with matches to set the houses on fire, and spears to scale the walls. They intended to go over the ice, but the channel being open, they were frustrated in their design. We were all paraded on Winter Hill, in order to run to their assistance as soon as the first gun was fired. But the statement that any of them fell through the ice is false. I hear my sisters have made a visit to Uncle Nesmith’s folks in Kenady*. I hope I am, your affectionate son, Robert Dinsmoor to William Dinsmoor.

Colonel Moore. We are stationed in a Brick house about half a mile down the river from the Town. This minute Abraham Plunkett* came in with fifteen letters, which revives my spirits. I am sorry that you had so much trouble with your letters — and Jonny says Colonel Moore carried my letters to Derry which he promised to leave at Capt. Gilmore’s. I am glad you are all well.; let mother know that I received her letter very joyfully. I have gotten but one letter from you since I came here. Last Friday night General Sullivan gave orders to his under officers to enlist a party of volunteers, such as were willing to make a push at Bunker’s hill, and burn a number of houses on Charleston neck; according to Capt Reynolds and Lieutenant Gregg and 21 members of our company went with Arms and Ammunition. The whole number that went was about three thousand, provided with matches to set the houses on fire, and spears to scale the walls. They intended to go over the ice, but the channel being open, they were frustrated in their design. We were all paraded on Winter Hill, in order to run to their assistance as soon as the first gun was fired. But the statement that any of them fell through the ice is false. I hear my sisters have made a visit to Uncle Nesmith’s folks in Kenady*. I hope I am, your affectionate son, Robert Dinsmoor to William Dinsmoor.

Medford January 19th 1776

My Dear Father,

As Colonel Gregg is going past your house, I cannot think of letting this opportunity pass without writing. No doubt you have heard of our Army being defeated at Canada, and all that went from here are either taken or killed — the thoughts of which seems to dampen the spirits of the most stout hearted among us. John Hunter came from Derry yesterday and said he overtook you on Spicket bridge on Saturday about eleven o’clock at night. I remain your loving son, Robert (“General Sullivan had made a special request that the militia men, as they were called, from New Hampshire should continue in the service one fortnight after heir first term was out — and the most of Capt. Reynold’s Company agreed to tarry, and among whom was Robert Dinsmoor, Jan, 19, 1776, in regard to this, in a letter to his mother, he says: ‘Had I attempted to return, In dishonor and disgrace…’ ”

(They were fearless in their cause, weren’t they?)

“Among the Windham men at Great Island, near Portsmouth, in fall of 1775, was Robert Dinsmoor, the “Rustic Bard.” The names of the rest not known. Windham had eleven men in the Continental army in December, 1775.* Soldiers enlisted for short terms of service, which accounts for the different number of men Windham had in the field at different times during the year. This account of General Stark’s prompt action was never before in print. The paymaster had neglected Stark’s men, and they were suffering for want of money. He sent a squad of men, arrested the paymaster, brought him to Medford, where his men were encamped, and showed him their suffering condition. This was done to relieve himself of blame from his men.”

“During the siege of Boston, on the 1st of December, 1775, General Sullivan, of New Hampshire, who was in command of the troops at ” Winter Hill,” in Charlestown, sent an urgent message to the New Hampshire authorities for more troops to take the places of the Connecticut troops, who refused to tarry longer, as their time of service had expired. The government answered the call, and Dec. 2, commissions were sent to various men in the different towns to enlist men for short terms of service. James Gilmore, of Windham, was commissioned as captain, Dec. 2, with Samuel Kelley, of Salem, first lieutenant, and David Gordon, of Pelham, as second lieutenant. Eleven Windham men were in this company.”

“We introduce a letter in possession of the author, from one of our men at the siege of Boston.”

LETTER OF JOHN MORISON TO HIS FATHER.

“Cambridge Jan. 9, 1775. Lieut. Samuel Morison.

Honored Father. — * * * Yesterday morning Samuel [his brother] went on Gen. Washington’s guard, and our camp was as still as usual till a little before sunset there was a stir for volunteers to go over the mill dam to Bunker Hill to burn 16 or 17 houses which the regulars used, and there were men enough before dark turned out volunteers and we were ordered to lay on our arms ready to turn out at the shortest notice but Capt. Gilmore, Isaac Cochran and myself went down about the rising of the moon and got to our end of the dam, but the party that went on was almost to the other end and so we staid about ten minutes. When the first matches were lighted and in a few minutes, there was light in every house, and then firing began from Bunker Hill at the houses with small arms in abundance and the balls went through the houses very fast. They shot some cannon towards the ploughed hill and some to the eastward of Cable Hill; I suppose some 20 in all, yet through the blessing of God we cant hear of one of our men amissing. There were nine or ten of the houses soon consumed, three or four are yet standing, and in one of them which was burnt they took five Regulars and one of their wives. They were sat down to take a game of cards and drink some punch, not knowing their danger, but in two or three hours their game was in Gen. Washington’s guard house while Samuel was on guard.” John Morison.”

“Captain Gilmore and his men remained with General Sullivan on Winter Hill till March 17, 1776, when the British evacuated the city, and they were discharged. John Morison, Samuel Morison, and Isaac Cochran were in his company. Robert Dinsmoor, “Rustic Bard,” was there; his uncle Robert Dinsmoor was there ; and while the latter was wheeling a wheelbarrow load of dirt, a cannon-ball struck and split open an apple-tree by his side, but did not harm him. Abram Planet or Plunket; Hadley and Thomas Gregg ; this latter was probably lieutenant of the company which was under the command of Captain Runnells, or Reynolds, of Londonderry. This company was at Medford in December, 1775, and remained till the latter part of January, 1776, when their term of enlistment is supposed to have expired, but at the urgent request of General Sullivan, most of the company re-enlisted for twelve days, among whom was the ” Rustic Bard.”