Capturing the Cannons at Fort Ticonderoga

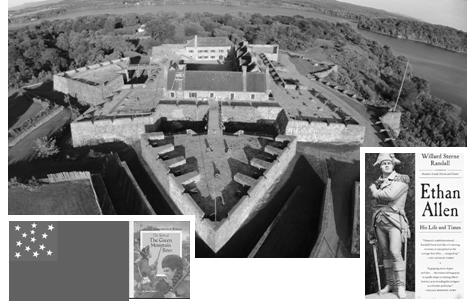

If you grew up in New England, one of your family road trips was likely to Vermont and New York, to see Fort Ticonderoga, and to explore the Ausable Chasm after ferrying across Lake Champlain.

“The capture of Fort Ticonderoga was the first offensive victory for American forces in the Revolutionary War. It secured the strategic passageway north to Canada and netted the patriots an important cache of artillery.”

“Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, together with Benedict Arnold, surprised and overtook a small British garrison at the fort, acquiring valuable weapons for the Continental Army. Arnold took command of Ticonderoga until he was relieved in June 1775.”

“Located at the confluence of Lake Champlain and Lake George, Fort Ticonderoga controlled access north and south between Albany and Montreal. This made it a critical battlefield of the French and Indian War. Begun by the French as Fort Carillon in 1755, it was the launching point for the Marquis de Montcalm’s famous siege of Fort William Henry in 1757. The British attacked Montcalm’s French troops outside Fort Carillon on July 8, 1758, and the resulting battle was one of the largest of the war, and the bloodiest battle fought in North America until the Civil War. The fort was finally captured by the British in 1759.”

“During the American War for Independence, several engagements were fought at the five-pointed star-shaped Fort Ticonderoga. The most famous of these occurred on May 10, 1775, when Ethan Allen and his band of Green Mountain Boys, accompanied by Benedict Arnold, who held a commission from Massachusetts, silently rowed across Lake Champlain from present-day Vermont and stormed the fort in a swift, late-night sneak attack.”

“Months later, George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, sent one of his officers, Colonel Henry Knox, to gather the artillery left at Ticonderoga and bring it to Boston. Knox organized the transfer of the heavy guns over frozen rivers and the snow-covered Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts. Mounted on Dorchester Heights, the guns from Ticonderoga compelled the British to evacuate the city of Boston in March of 1776.”

“The capture of Fort Ticonderoga was the first offensive victory for American forces in the Revolutionary War. It secured the strategic passageway north to Canada and netted the patriots an important cache of artillery. n 1775, Fort Ticonderoga is garrisoned by a small detachment of about 50 men and has fallen into disrepair, but its value—both for its location and the arms it houses—is well known. Patriot Benedict Arnold persuades the Massachusetts provisional government to give him a commission to command a secret mission to capture the fort. But Arnold soon learns that Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys are already on their way north towardward Ticonderoga with the same intention. Arnold is warned that although Allen has no official sanction for his planned attack, his loyal men are unlikely to take orders from anyone else. Arnold feels that he should lead the expedition based on his formal authorization to act from the Massachusetts government. He and Allen come to an agreement about sharing command, despite the objections of some of Allen’s men. Ultimately, their force includes about 100 of Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys and 50 other men recruited throughout Connecticut and Massachusetts.”

“By 11:30 p.m. on May 9, the men are ready to cross the lake from what is now Vermont to Ticonderoga. The small boats do not arrive until 1:30 a.m. and they cannot accommodate the entire force. Eighty-three of the Green Mountain Boys make the first crossing with Arnold and Allen. As dawn approaches, Allen and Arnold, worried about losing the element of surprise, decide to attack with the men at hand.

American victory. Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, together with Benedict Arnold, surprised and overtook a small British garrison at the fort, acquiring valuable weapons for the Continental Army. Arnold took command of Ticonderoga until he was relieved in June 1775.”

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/fort-ticonderoga-1775