Black History in New England

Nicholas Vicksham African-American Patriot

Nicholas Vicksham (Vixtrom, Vintrom) was an African–American from Windham NH., who fought in Captain James Carr’s Company as part of Colonel Poor’s Regiment (later Hale) during the Saratoga campaign.

Joseph Cutshall-King in a Post Star article from March 2, 2020 says “American patriot blacks fought at several key engagements in Burgoyne’s campaign. The Battle of Hubbardton, Vermont, on July 7, 1777, is a case in point. Simeon Grandison of Scituate, Mass., fought at the battle, but it not known with what regiment he served. Asa Perham (also spelled Purham and Pearham) served and fought that day with Col. Nathan Hale’s 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, as did Nicholas Vintrom. Vintrom also spelled Vixtrom, who was captured by the British, but survived. The Battle of Hubbardton by Col. John Williams notes the presence of four black patriot soldiers at that battle. Titus Wilson of Peterborough, N.H., fought with Col. Cilley’s Regiment. Wilson was wounded and captured, and died that same day…”

“You’ve probably surmised that black patriots, such as Minutemen Peter Salem and Cuff Whittemore, fought at so many of the pivotal Revolutionary battles. For example, both Salem and Whittemore faced Burgoyne twice: once at Bunker Hill in 1775 and again at Saratoga in 1777. I’ll end with a recounting of Whittemore’s bravery. Whittemore fought at Saratoga, where British forces captured him. Brought to Burgoyne’s tent, he was ordered by a British regular to take Burgoyne’s horse, as if to hold the reins like a groom or some such thing. Whittemore did, indeed, take Burgoyne’s horse, but not as ordered. Instead he mounted it and, amidst whizzing musket balls, sped off to freedom on Burgoyne’s own steed! Whittemore added an ultimate insult to the overall injury of defeat Burgoyne would suffer at Saratoga.”

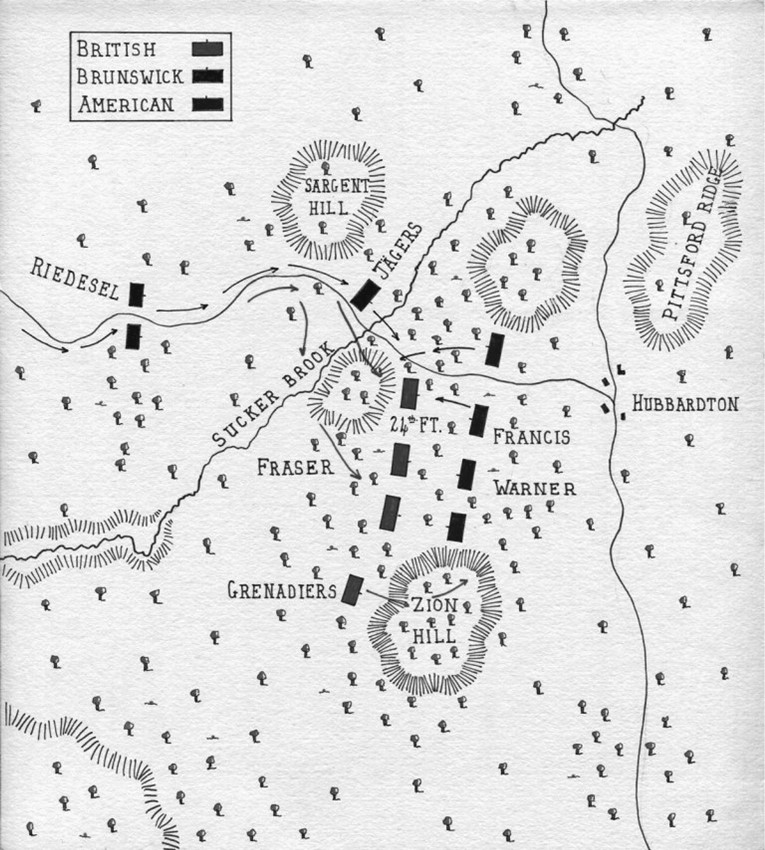

Battlefield.org summarizes the battle at Hubbardton this way: “During the 1777 Saratoga Campaign, there were several crucial limited engagements that played a role in slowing down General John Burgoyne’s 8,000-man invasion force as it made its way south from Canada to rendezvous with other British forces near Albany, New York. One of those places was Hubbardton located in present day Vermont. The British attacked the American rear guard, which had abandoned Fort Ticonderoga without firing a shot after the British placed cannons on the hills overlooking the fort. With Fort Ticonderoga made untenable, General Arthur St. Clair ordered the fort evacuated on July 5, 1777.”

“With intelligence in hand that the Americans had left their defensive position at Fort Ticonderoga and were headed south, the British opted to take advantage of the situation. Burgoyne’s adjutant, General Simon Frasier, pursued the Americans, catching up with them on July 7 at Hubbardton. Elements of Saint Clair’s rear guard had encamped at Hubbardton and were taken by surprise by the British, reinforced by a detachment of Brunswick Grenadiers and Jägers led by General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel. The Americans put up stiff resistance, and almost succeeded in turning the British flank, only to have the Brunswick Grenadiers arrive on the field, singing Hymns as they crashed into the American flank, staving off a British defeat. Joining in the fight for the Americans was Colonel Seth Warner, a grizzled Veteran of the French and Indian War and his band of Green Mountain Boys. These were the Americans who provided the heavy fighting on the American side.”

“While many Americans were taken prisoner and marched back to Fort Ticonderoga for confinement, the bulk of Saint Clair’s army was able to escape further south along the Hudson. The result was a British tactical victory, but an American strategic victory.” According to Battlefield.org, 2,230 troops were engaged in the battle, 1,200 Americans, 1,030 British. There were 557 casualties: Americans: 367– 41 killed, 96 wounded, 230 missing or captured. British: 190– 49 killed, 141 wounded. I have the names of four African-Americans at the Battle of Hubardton including our Windham man, Nicholas Vicksham: “Four black American soliders took part in the Battle of Hubbardton: Titus Wilson (Willson), Peterborough, NH., Col. Cilley’s Regiment. He was wounded, captured and died at Hubbardton on the day of the Battle. Simeon Grandison, Situate Massachusetts, regiment not known, Asa Perham, Col. Hale’s regiment. Nicholas Vintrom (Vixtrom) Col Hales’s regiment, captured July 7, John Rees, in his book “They Were Good Soliders” mentions a fifth African-American at Hubbardton, “Scipio Bartlett enlisted in Colonel Ebenezer Francis’s Regiment in February 1777 and fought at the Battle of Hubbardton in Vermont that July, where Colonel Francis was killed. Bartlett added this postscript: ‘I further on oath declare that I was emancipated at the commencement of the Revolutionary War and was a free man during my whole term of service… I am a Black man—but free—and of the age of sixty-six years…’” So at least five African-American’s fought at Hubbardton.

Unfortunately, we know very little about Nicholas Vicksham, as his name is spelled on the marble plaque in the Windham Museum, memorializing his service in the Revolutionary War. We don’t know whether he was a freed black or a slave since both lived in Windham. Morrison records that in July 14, 1776 that, “We the subscribers acknowledge that we have each of us received the sum of six pounds sixteen shillings lawful money from the selectmen in Windham in behalf of the town as a reward to serve on the Continental army for the space of five months: Allen Hopkins, John McCoy, John Jobe, (Joel?) William Dickey Sergt., James Gilmore, David Davidson, Samuel Dinsmoor, Robert Dinsmoor, Nathaniel Hemphill and Nicholus Vickstrum.” The fact that “Vickstrum” enlisted with slave-owner, Nathaniel Hemphill, leads to questions with no answers…was Vickstrum a slave of Hemphill’s or a free man? We also know from the regimental roles that he was 28 years old, stood five foot ten inches tall upon enlistment and that he received a twenty dollar bounty. Here is what we do know from Morrison: “Windham May 8, 1777.—There is enlisted out of Windham, William Darrah, Robert Stuart, in the Continental Army to serve for three years. Enlisted with Lieutenant Cherry, John Joal (Job?), and Nicholas Vicksham.” (“On November 8, 1776 Ensign Cherry was commissioned a Lieutenant in Capt. James Carr’s Co. in 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, Col. Nathan Hale commanding.”) “Lieutenant Cherry, from Londonderry was in Capt. James Carr’s company of Colonel Nathan Hale’s Second NH. Regiment. Morrison says, “Vicksham, was taken prisoner at the battle of Hubbardton, and was never heard from afterwards.”

We know little of the other commanders at Hubbardton. Colonel Ebenezer Francis was like Warner a huge man with some military experience, for he had commanded a regiment at the siege of Boston. He commanded a Massachusetts regiment at Hubbardton, was killed at the head of his men, and buried by the Hessians. Colonel Francis was a fine example of the patriotic citizen-soldier. He died-as every true soldier would wish to die-in the forefront of the battle his face to the foe. “No man died on that field with more Glory than he yet many died and there was much Glory.”

“Colonel Nathan Hale was still somewhere down the hill near Sunker Brook with a remnant of his regiment, including Captain James Carr’s company, (Vicksham’s Company), Captain Caleb Robinson, and several stragglers and invalids. Despite being taken by surprise, Hale’s men had done their best to delay the crush of redcoats. However, as a fighting unit they ceased to exist, the men, faced with overwhelming odds, had slipped into the woods and continued the fight individually and in small groups…” According to another account, “…Colonel Nathan Hale, at the first onslaught of the enemy, retired with his regiment, as many of his men were sick and exhausted; he was overtaken on the road to Castleton and surrendered. Colonel Hale was bitterly criticized for his action and asked for a court martial, but before it could be granted, he was taken prisoner and died on Long Island. He was thirty-seven years old.” It is likely then this is how Nicholas Vicksham was captured by the British at the battle. What we also know is he never returned from the war and likely perished in captivity. Hadden’s version confirms

Ethan Allen’s statement, that Hale surrendered to ” an inconsiderable number of the enemy ;” for Allen, in writing of the affair at Hubbardton, says: — “It was by this time dangerous for those of both parties who were not prepared for the world to come ; but Col. Hale being apprised of the danger, never brought his regiment to the charge, but left Warner and Francis to stand the blowing of it, and fled, but luckily fell in with an inconsiderable number of the enemy, and to his eternal shame, surrendered himself a prisoner.” A letter, evidently written by a member of Col. Cilley’s New Hampshire Regiment (which was on the retreat from Ticonderoga, but not in the engagement at Hubbardton), dated Moses’ Creek, July 17th, 1777, and indorsed, ” Letter from Cogan to Gen’l John Stark,” &c., to be found in vol. 8, of the New Hampshire State Papers, page 640, gives a very graphic account of the disorder and confusion attending the retreat from Ticonderoga. Although his regiment was not in the action, Cogan writes as if he had been ; and undoubtedly many, who had straggled from their regiments, were with the rearguard.

“Our situation puts me in mind of what I have heard you often say of Ticonderoga. Such a Retreat was never heard of since the Creation of the world. I was ordered about five of the Clock in the afternoon to draw forty-eight Rounds per man :afterwards, nine days allowance of provision which I completed about 2 of the clock in the morning, and about the time I got home the Tents were struck, and all was ordered to retreat ; but it was day light before we got below your old house \ such order surprised both officers & soldiers ; then they wished for General Sullivan to the Northern army again ; they left all the Continental clothing there ; in short every article that belonged to the army ; which if properly conducted might be easily saved. Surely we were fifty thousand times better off than General Sullivan was in Canada last year ; our men was in high spirits, and determined to a man to stick by the lines till they lost their lives, rather than quit so advantageous a Post ; Drove us a long two or three & thirty miles that day, till the Rear Guard got to Bowman’s Camp; the men being so fatigued were obliged to stay, and were attacked in the morning by the Regulars, who travelled all Night, and just got up by the time we were beginning to march in a disorderly manner; our men being in confusion, and made no great of a Battle. But some behaved & some did not. Col°. Reed acted his part very well. Col°. Hale they said did not. Col°. Hale is either kill’d or taken. Little Dwyer behaved like a lusty fellow & died in the Bed of Honor ; as nearly as I could conjecture, we had odds of a thousand that attacked them ; our main body was within six miles of us, the Indians took & killed a vast number of our men on their Retreats ; then was hurried at an unmerciful rate thro’ the woods at the rate of thirty-five miles a day, oblidg’d to kill oxen belonging to the Inhabitants wherever we got them; before they were half-skinned every soldier was obliged to take a bit & half Roast it over the fire, then before half-done was obliged to March, — it is thought we went 100 miles for fear of seeing a Regular (I mean out of the way) there never was a field officer consulted, whether we should retreat or not, which makes them very uneasy ; so that the blame of our Retreat must fall on our Commanders; never was soldiers in such a condition without cloaths, victuals or drink & constantly wet. Caleb* and I are just as our mothers bore us without the second shirt, the second pair of shoes, stockings or coats, — but however its all in the Continent. Caleb does vastly better than he ever did with you. Col. Cilley is very fond of us. Indeed, I suppose we are pretty diligent for the most part. Give my compliments to Peggy, Arch & Jenny & Martha.

” I am Respects Yours,

“N. B. The officers lost their Baggage, writings & all. The

Rear Guard were mostly Invalids, and our Gen” took away

the main Body, and even refused to send assistance when the

Cols, begged him to do it.”

“Indorsed — ‘Letter f.om Cogan to Gen’ John Stark,’ “

*” Caleb was the eldest son of Gen. John Stark. — Ed.

“Although Hale was the official commander of the 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, he was delayed in joining Warner because of the large number of sick, disabled, and stragglers, who St. Clair had assigned to his regiment. (In the entire Northem Army, 532 men were listed as “Sick, Present,” or roughly eighteen percent of the rank and file as of June 28, 1777. These were the men who made Hale’s fob so difficult. G.W. Nesmith states in his book New Hampshire at Hubbardton that Hale was six miles behind the other American troops. Finally, when Francis arrived about 4 p.m., Warner took command of the entire rear guard. Upon Hales’s arrival at the bivouac area that aftemoon, the three commanding officers gathered at the log cabin of John Selleck, which stood at the junction of the military and Castleton roads at what is now East Hubbardton. “

“Colonel Hale perhaps had one of the most difficult parts to play in the Battle of Hubbardton. General St. Clair had placed him in charge of the invalids, walking sick, wounded, and stragglers, including some who were intoxicated, from the retreating Northern Army in the forced march from Mount Independence. By the time they finally reached Hubbardton late on the afternoon of July 6, this unorganized group may have numbered three hundred. They were from all ten of the regiments in St. Clair’s rapidly retreating army.”

“When Colonel Hale finally came up with his group, Warner, now in overall command of the reinforced rear guard, assigned them to an area well west of the military road and along Sucker Brook, downstream, where they could clean themselves up and rest. They were attached to Captain Carr’s company of Hale’s 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, already in place as an outpost to secure the extreme left flank on the west. This position was near the site of the Old Manchester Farm road, a likely approach by the British.”

“A number of the soldiers were recovering from measles and were very weak. Ebenezer Fletcher, a fifer in Carr’s company, writes, “Having just recovered from the measles and not being able to march with the main body [Northern Army] I fell in the rear.” Some no doubt suffered from dysentery, diarrhea, hangovers, and other troop disorders, as well as the aftermath of measles. The day was reported as excessively hot, and the distance marched was well over twenty miles at a grueling pace. After seeing to his group of sick and exhausted men, Hale reported to Warner at the Selleck cabin on the south side of Monument Hill.”

“The next morning, July 7, about 7:00 Captain Carr’s company and the group of sick and stragglers were surprised by the British as they attacked across Sucker Brook. Ebenezer Fletcher, continuing his narrative, reported the opening of the battle as he observed it first hand:

“The morning after our retreat, orders came very early for the troops to refresh and be ready for marching. Some were eating, some were cooking, and all in a very unfit posture for battle. Just as the sun rose [down deep in a valley, with steep hills to the east, this could well have been about 7:00], there was a cry “The enemy are upon us.” Looking around I saw the enemy in line of battle. Orders came to lay down our packs and be ready for action. The fire instantly began. We were but a few in number compared to the enemy. At the commencement of the battle, many of our party retreated back into the woods. Capt. Carr came up and says, “My lads advance, we shall beat them yet.” A few of us followed him in view of the enemy. Every man was trying to secure himself behind girdled trees, which were standing on the place of action. I made shelter for myself and discharged my piece. Having loaded again and taken aim, my piece misfired. I brought the same a second time to my face, but before I had time to discharge it, I received a musket ball in the small of my back, and fell with my gun cocked…’

“Fletcher hid himself under a tree but was discovered by the British after the Battle, brought into camp, and treated well by two doctors who told him that he had some prospect of recovering. It appears to have been this relatively isolated unit and Hale’s group of sick and stragglers out on the extreme west or left flank that were surprised, suggesting strongly that enemy scouts and Indians “took of [off] a Centry . . .” during the night, as was reported by Captain Greenleaf. The Indians had captured or tomahawked the sentry or picket so that the British attack, which came later, came without warning. As explained by Fletcher, these troops withdrew, firing at the British from behind trees as they did so. They withdrew into Warner’s sector and across the Castleton road, where they were defeated, with many killed and wounded and with many prisoners taken by the pursuing and overrunning British troops under Lindsay and Acland.”

“The location of Colonel Hale during this early phase of the battle is not clear. Since he was still responsible for the sick and stragglers group in Captain Carr’s area, and since Carr was one of his subordinate company commanders, it would appear that he would have exercised early morning responsibilities there, and no doubt he did so, and may have been midway between his regiment on Monument Hill and his group of invalids and stragglers down at Sucker Brook when the British attacked.

“In any event, Hale had placed his understrength 2nd New Hampshire regiment under the temporary command of Major Benjamin Titcomb, his second in command. Titcomb brought the regiment to Monument Hill while Hale was struggling with his sick and straggler group in the rear. Titcomb was assigned the northern sector of the hill, on the American right flank, the first to face the British assault.”

“On July 7, shortly after 7:00, as Warner and Francis were assembling for marching, Titcomb had not yet assembled Hale’s regiment when the British attacked. One soldier there testified that “the action began on Francis’s right, which soon gave way.” It is likely that Hale’s troops, temporarily under Titcomb, had not as yet formed for marching and were the ones who initially gave way. But although they were in greater disarray than the other two regiments, the 2nd New Hampshire men apparently recovered and held out as long as the other two commands, suffering more disabling wounds than the other two combined. After withdrawing behind the high log fence, elements reorganized, and in company with Francis’s troops attacked the British left flank that had become exposed. The Americans were bringing pressure on the British left and were about to get behind them when the Germans attacked them from the front, flank, and rear. At this point the Americans disengaged and scattered east toward Pittsford ridge.”

“Since Hale’s men did not leave any description of the action in their sector, our presumption of activity is based upon the pension records of disabling wounded among Hale’s men and the killed, as well as upon Bird’s statement that Hale’s men were on the right flank. That Hale had a dual mission there can be no doubt, which may explain the several conflicting accounts as to his actions and locations.”

“Hale and about seventy men were surrounded after the battle and captured when threatened by a ruse. Hadden, recognized as the authority on Hale, wrote, “As proof of what may be done against Beaten Battalions while their fears are upon them, an officer and 15 men detached for the purpose of bringing in Cattle fell in with 70 Rebels, affecting to have the rest of the party concealed and assuring them they were surrounded [by a larger number], they surrendered their arms and were brought in [as] prisoners.”

“By the time Hale and his men were captured, the firing had ceased. Certainly, a detachment would not be looking for cattle in the vicinity of a battlefield when the shooting was in progress. Hale and his men, many of whom were seriously wounded, were like the rest of the retreating Americans trying to reach a road or trail across the mountains toward Rutland. There can be no doubt that Hale acted to save the lives of his men. Actually, the feigning of a larger concealed force was more a reality than a deception when we consider that von Breymann’s 1,000 Germans had just arrived at the very close of the most violent phase of the Battle.”

“In Travels through the interior parts of America, Thomas Anburey, a member of Burgoyne’s army wrote about the action with Colonel Hale: “The Indians under the command of Captain Frazer, supported his company of marksmen (which were volunteer companies from each regiment of the British) were directed to make a circuit on the left of our encampment, to cut off the retreat of the enemy to their lines: this design, however, was frustrated by the impetuosity of the Indians who attacked to soon, which enable the enemy to retire with little loss. General Phillips took Mount Hope, which cut off the enemy…”

“During the battle (at Hubbardton) the Americans were guilty of such a breach of military rules, as could not fail to exasperate our soldiers. The action was chiefly is the woods, interspersed with a few open fields. Two companies of grenadiers, who were stationed in the skirts of the woods, close to one of the fields, to watch the enemy did not outflank the 24th regiment, observed number of Americans, to the amount near sixty, coming across the field, with their arms clubbed, which is always considered to be a surrender of prisoners of war. The grenadiers were restrained from firing, commanded to stand with their arms, and show no intention of hostility: when the Americans got within ten yards, they in an instant turned round their muskets, fired upon the grenadiers, and rum as fast as they could into the woods; their fire killed and wounded a great number of men, and those who escaped immediately pursued them, and gave no quarter….” “…we laid upon our arms all night, and the next morning sent back the prisoners to Ticonderoga, amounting to near 250. A very small detachment could be spared to guard them, as General Fraser expected the enemy would have reinforcements from the main body of the army…He told the colonel of the Americans (Hale), who had surrender himself, to inform the rest of the prisoners, that if they attempted to escape, no quarter would be shown them, and that those who might elude the guard, the Indians would be sent in pursuit to scalp them…”

1) https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/hubbardton

3) Great video about the Battle of Hubbardton by Howard Coffin; You-tube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIm44hoKuu8

4) Animated map of battle: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pdCdykHbP4s&t=11s

5) https://historicsites.vermont.gov/hubbardton-battlefield/exhibits

https://historicsites.vermont.gov/hubbardton-battlefield/research

6) Detailed description of battle: https://historicsites.vermont.gov/sites/histsites/files/documents/Hubbardton%20Battlefield%20Research%202018.pdf

7) https://mountindependence.org/visit/

8) https://vermonthistory.org/journal/78/VHS780101_1-14.pdf

9) http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/battle-of-hubbardton-july-7-1777/

10) Battle of Hubbardton, Bruce Ventor: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00XZPQOD4?ref_=k4w_oembed_UYFb0SULw5xims&tag=revolution035-20&linkCode=kpd

11) https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/education/upload/Boston%20Lesson.pdf

12) https://www.amrevmuseum.org/read-the-revolution/they-were-good-soldiers

13) Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, 1856, William C. Nell.

14) https://www.nhssar.org/PdfFiles/NHRevWarDead.pdf

16) http://www.bobfarley.us/1777freedomsgateway/1777printbooks/Battle%20of%20Hubbardton.pdf

17) https://vermonthistory.org/journal/misc/BattleOfHubbardton.pdf

18) https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/07/tis-evacuation-and-the-battle-of-hubbardton/

19) Hadden’s Journal of Burgoyne’s Campaign: https://archive.org/details/haddensjournalor00hadd/page/n603/mode/2up

20) Prisoner of War Ships: https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/prisoners-of-war/

22) https://archive.org/details/rebelprisonersat00mche

23) Interior Travels Through America: https://archive.org/details/travelsthroughin_01anbu/page/206/mode/2up

24) https://www.myrevolutionarywar.com/battles/770707-hubbardton/

25) Narrative of Ebenezar Fletcher: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N25420.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext