Canonbie, Canobie, and Cannobie

Johnnie Armstrong

Johnnie Armstrong of Ginockie was a powerful leader who ruled a vast area along the Scottish Border. He is perhaps one of the best known figures among the Border reivers. A stirring ballad was written about him soon after his death and he was further romanticized in the nineteenth century writings of Sir Walter Scott.

Johnnie became very rich and powerful and could put 3000 horsemen in the field. Very little is known of his early life but it was rumored that he made a fortune while at sea then returned to the Esk River Valley and became a powerful leader.

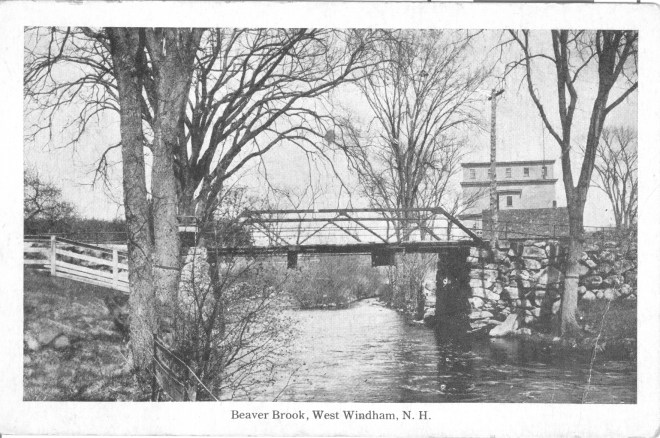

Armstrong became known as “Black Jok” because he specialized in blackmail or black rent. “It was said that there was not one English place of prominence between his home at Hollows Tower, known as Gilnockie and east Newcatles which did not pay protection money to Black Jok.” The “rent” was paid to insure they would be protected from raids by both Armstrong and other Border reivers. Armstrong operated for some years under the protection of Robert, the 5th Lord Maxwell who was the Scottish West March Warden. The six Marches consisted of three on the Scottish side of the border and three on the English. The Marches were established by Scotland and England to supervise the unruly border areas. Maxwell, was one of Scotland’s great feudal barons. He was in a long lasting feud with the Johnstone Clan. Maxwell had engaged the Armstrongs as extra troops the fight the Johnstones. He subsequently owed the Armstrongs protection. Although responsible for keeping the reivers under control, Maxwell “looked the other way” as the Armstrongs and their allies, the Nixons, Elliots and Crosiers went about their reiving. Black Jok burnt Netherby in Cumberland in 1527, in return for which William Dacre, 3rd Baron Dacre burnt him out at Canonbie in 1528; and Gavin Dunbar, the Archbishop of Glasgow as well as Chancellor of Scotland, intervened with an excommunication for Armstrong. In a way the power and wealth of Armstrong was an embarrassment for the young King James V. Maxwell began to fear the power of Johnnie Armstrong and his lack of loyalty. Henry VIII was putting diplomatic pressure on James V to put an end to the lawlessness that was rampant in the Borders region. At the time there was a truce of sorts between England and Scotland and Black Jok and other reivers flouted the peace with their lucrative harassment of the English Border. James V wanted to subjugate the power of the Scottish Border clans. James V moved south to the Scottish Borders in June 1530 intent on proving to the Border clans that it was he who ruled in Scotland, including the Borders. He first executed other reiving clan leaders and then headed south to deal with Armstrong. It is said that James V tricked Armstrong into meeting him at Carlenrig. Some sources say that a “loving letter” was sent inviting him to hunt with the king. Whatever the case, a shrewd Johnnie Armstrong would never have agreed to meet the king without a guarantee of safe conduct.

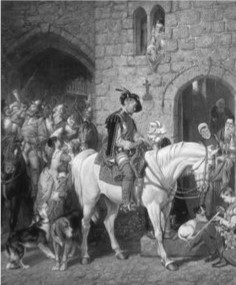

According to the “Ballad,” Armstrong made a great show, dressed in his finery as would have befitted any court and accompanied by an entourage of about twenty-four Lairds and retainers, including Elliots, Littles and Irvines. Perhaps the confusion over the actual numbers hanged with Armstrong, twenty-four, thirty-six or fifty, stems whether or not the retainers were also hanged. Johnnie Armstrong sported a hat from which hung nine gold and silver tassels, and but for the sword of honor and a crown, he could have been King. When it became clear that he was to be hanged John Armstrong declared himself a subject of James his liege and stated he had only raided the English. The most famous lines, oft quoted by Sir Walter Scott, were uttered by Armstrong, when the extent of the King’s duplicity was revealed:

“To seek hot water beneath cold ice

Surely it is a great folly

I have asked grace at a graceless face,

But there is none for my men and me.”

He is also reputed to have said, “Had I known, Sire, that you would take my life this day, I should have stayed away and kept the Border in spite of King Henry and you, both. For I know that Henry Tudor would be a blithe man this day to know that John Armstrong was condemned to die. Which proves who lacks in judgement, does it not?” Nevertheless, all was in vain as he and his men were led to the trees around Carlenrig and hanged from the back of their mounts.

Legend has it that the trees at Carlenrig, where Armstrong and his followers were hanged, withered and died, and none have grown there since.”

In the aftermath of the hanging, Robert, Lord Maxwell, who came to fear Armstrong’s burgeoning power benefited from Armstrong’s death. On 8th July 1530, three days after the death, Maxwell received into his hands all the property that had belonged to Johnnie Armstrong.

Being the reivers that they were, you can be sure that the Armstrongs had their revenge. Twelve years later, in 1542, James V was to die, some say of a broken heart, following the rout of the Scottish army at the Battle of Solway Moss which took place eight days after the birth of his daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots. Some of the Armstrongs joined the English army in dealing a mortal blow to the Scots as they vainly tried to cross the river Esk at Longtown. It was the Armstrongs who picked off the remnants of the Scots army as they fled in panic north through Liddesdale.

.